Position, Transportation, and Resources: Japan's Potential and Strategic Choices Under Analytical Geopolitics

Published 2025-07-07

Keywords

- Japan,

- Geopolitical Analysis,

- Potential,

- Maritime Transportation,

- Resources

How to Cite

Copyright (c) 2025 Nuno Morgado, Takashi Hosoda

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Accepted 2025-07-02

Published 2025-07-07

Abstract

Japan is a very poor country in terms of natural and mineral resources. Consequently, it remains heavily dependent on maritime transportation. Japan’s proximity to a competing China, the ever-strengthening Sino-Russian partnership, and an aggressive North Korea constitute a hostile regional environment. This article offers an in-depth analysis of Japan’s capabilities (i.e., potential), predominantly demonstrating the weaknesses of the country. We argue that the flaws associated with Japan’s potential can be explained by both (i) geomisguided Japanese geopolitical agents, and (ii) the Japanese pacifist strategic culture. We deductively apply the model of analytical geopolitics. Our findings are that Japanese geopolitical agents are “geomisguided” as they have pursued policies of insufficient stockpiling and disregarded Japan’s dependence on the sea lanes of communication. Furthermore, Japanese public opinion does not sufficiently grasp the current threats Japan faces, and this fact limits the capacities of Japanese geopolitical agents. The paper addresses a gap in the literature by applying an innovative methodological analytical approach.

Highlights:

- Japan is heavily dependent on maritime transportation, and the number of Japanese-flagged vessels is insufficient.

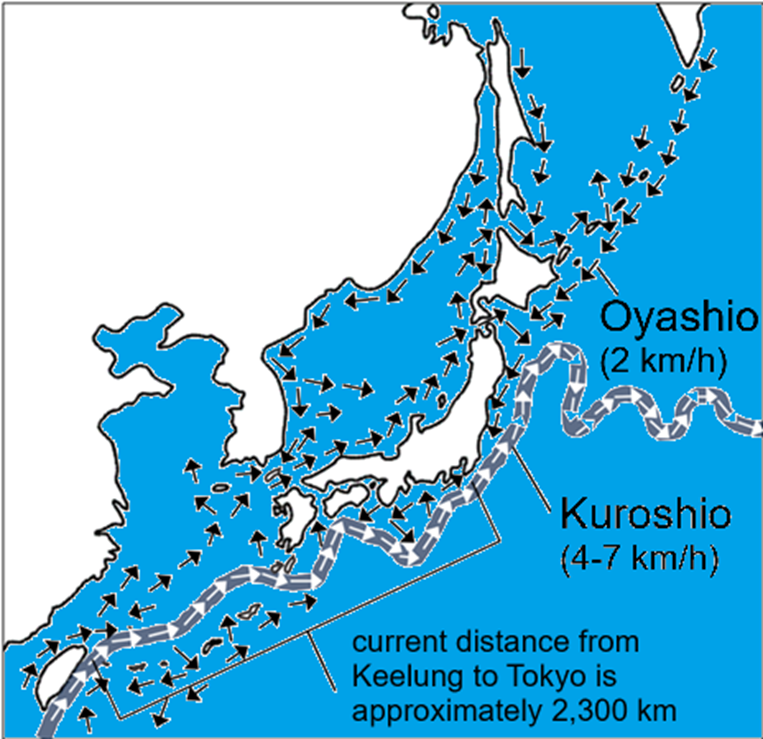

- Japanese maritime currents have a military impact concerning floating mines.

- Postwar Japanese pacifism clashes with security imperatives and encourages weaknesses in Japan’s potential.

Downloads

References

- Agency for Natural Resources and Energy. (2024). Energy white paper 2024. https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/about/whitepaper/2024/pdf/3_1.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Berger, T. (1998). Cultures of Antimilitarism: National Security in Germany and Japan. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Bukh, A. (2014). Revisiting Japan’s Cultural Diplomacy: A Critique of the Agent-Level Approach to Japan’s Soft Power. Asian Perspective, 38(3), 461–485. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43738099

- Douglas, A. J. (2023). Get Serious About Countering China’s Mine Warfare Advantage, Proceedings, 149(6-1). https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2023/june/get-serious-about-countering-chinas-mine-warfare-advantage

- Erickson, A.S., Murray, W.S. & Goldstein, L.J. (2009). Chinese Mine Warfare: A PLA Navy 'Assassin's Mace' Capability. CMSI Red Books, 3, 1-93. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cmsi-red-books/7/

- Galic, M. (2024, August 22). How Fumio Kishida Shaped Japan’s Foreign Policy. United States Institute of Peace, https://www.usip.org/publications/2024/08/how-fumio-kishida-shaped-japans-foreign-policy

- Graham, E. (2006). Japan’s Sea Lane security, 1940-2004: A matter of life and death? Routledge.

- Gustafsson, K., Hagström, E., & Hanssen, U. (2018). Japan’s Pacifism Is Dead, Survival, 60(6), 137-158. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2018.1542803

- Haines, S. (2014). 1907 Hague Convention VIII Relative to the Laying of Automatic Submarine Contact Mines, International Law Studies, 90,

- –445. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1005&context=ils

- Hanssen, U. & Koppenborg, F. (2023). More Weapons than Windmills: Japan's Military and Energy Policy Response to Russia's Attack on Ukraine,

- Czech Journal of International Relations, 58(2), 133–148. https://doi.org/10.32422/cjir.733

- Heginbotham, E., and Samuels, R. J. (1998). Mercantile Realism and Japanese Foreign Policy. International Security, 22(4), 171–203. https://doi.org/10.2307/2539243

- Heginbotham, E. & Samuels, R. J. (2018). Active Denial: Redesigning Japan's Response to China's Military Challenge. International Security 42(4), 128–169. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00313

- Heginbotham, E. Leiter, S. & Samuels, R. J. (2023). Pushing on an Open Door: Japan’s Evolutionary Security Posture, The Washington Quarterly, 46(2), 47-67. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2023.2226992

- Hosoda, T. (2021). National Identity, National Pride, and ‘Armed force’ in Japan: How to verify the existence of pacifist culture in Japan. In: Kol-mas. M. & Sato. Y. (Eds.), Identity, culture, and memory in Japanese Foreign Policy (pp. 103-130). Peter Lang.

- Iizuka, R. and Kikuchi, T. (2014). Current Situations and Critical Issues of Primary Food Supply in Tokyo. European Journal of Geography, 5(2), 61–76. https://eurogeojournal.eu/index.php/egj/article/view/504

- Ikeda, T. (2023). Kaijoujieitai ni kyousyu yourikukan wa hitsuyou ka? [Does JMSDF need amphibious assault ships?], Ship of the World, 1007, 99–103.

- Japan Maritime Public Relations Center. (2024). Shipping Now 2024-25 - Japan’s maritime transportation,

- https://www.kaijipr.or.jp/assets/pdf/shipping_now/allpage2024.pdf

- Johnston, A.I. (1995). Thinking about Strategic Culture. International Security, 19(4), 32-64. https://doi.org/10.2307/2539119

- Kabuta, F. (2012). Shokuryou no ryouteki risuku to kadai [Food risks in terms of sufficiency], Journal of Rural Economics, 84 (2), 80–94. https://doi.org/10.11472/nokei.84.80

- Kaijo Rodo Kyokai [The Maritime Labor Association]. (1962). Nihon shosentai senji sonanshi [Wartime maritime disasters of the Japanese mer-chant fleet], Tokyo: Seizando-Shoten.

- Katzenstein, P. (1996). Cultural Norms and National Security: Police and Military in Postwar Japan. Cornell University Press.

- Koga, K. (2018). Japan’s strategic interests in the South China Sea: beyond the horizon? Australian Journal of International Affairs, 72(1), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2017.1399337

- Kosaka, M. (1965). Kaiyo Kokka Nihon no Koso [The concept of Japan as a maritime nation]. Chuo Koronsha.

- Kotani, T. (2006). Sea-lane Boei [Sea-lane defense: The dynamics of U.S.-Japan naval cooperation during the Cold War]. Doshisha Law Review, 58(4), 179–207.https://doi.org/10.14988/pa.2017.0000010964

- Kotani, T. (2024). Dai 25 sho: Nihon no kaiyou anzen hosho seisaku—FOIP, QUAD, Higashi Shina Kai, Minami Shina Kai [Japan's maritime security policy—FOIP, QUAD, East China Sea, South China Sea]. In M. Tsuruoka (Ed.), Chiseigaku jidai no Nihon [Japan in the age of geopolitics] (pp. 207–214). Konrad Adenauer Foundation.

- Lim, G. & Xu, C. (2023). The Political Economy of Japan’s Development Strategy under China-US Rivalry: The Crane, the Dragon, and the Bald Eagle. Chinese Economy, 56(4), 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/10971475.2022.2136692

- Masuda, H. (1986). Dai 6-shō: Senjika no kotsu・unyu—1938–1945 [Transportation and logistics during wartime—1938–1945]. In Kotsu・unyu no hattatsu to gijutsu kakushin: Rekishiteki kosatsu [The development of transportation and logistics and technological innovation: A historical study]. Tokyo: United Nations University.

- Medzini, A. (2017). The Role of Geographical Maps in Territorial Disputes Between Japan and Korea. European Journal of Geography, 8(1), 44–60. https://eurogeojournal.eu/index.php/egj/article/view/279.

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. (2021). Area of cultivated land in 2021. https://www.maff.go.jp/j/tokei/kekka_gaiyou/sakumotu/menseki/r3/kouti/index.html#:~:text=%E8%AA%BF%E6%9F%BB%E7%B5%90%E6%9E%9C%E3%E381%AE%E6%A6%82%E8%A6%81,%EF%BC%880.5%EF%BC%85%EF%BC%89%E6%B8%9B%E5%B0%91%E3%81%97%E3%81%9F%E3%80%82

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. (2023). Food self-sufficiency rate in FY2022. https://www.maff.go.jp/j/zyukyu/zikyu_ritu/012.html

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. (2023, August). Fusokuji no shokuryō anzen hoshō no kentō ni tsuite [Considerations on food security in the event of unforeseen circumstances] https://www.maff.go.jp/j/zyukyu/anpo/attach/pdf/kentoukai-6.pdf

- Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI). (2024), Nihon no enerugii 2024 [Energy in Japan 2024]. https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/about/pamphlet/pdf/energy_in_japan2024.pdf

- Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. (2025). Enerugii kihon keikaku [The Seventh Basic Energy Plan]. https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/category/others/basic_plan/pdf/20250218_01.pdf

- Miyagi, T. (2015). San Francisco kouwajoyaku to Yoshida rosen no sentaku [San Francisco Peace Treaty and Choice of Direction of Yoshida Poli-cy], Kokusai Mondai [International Affairs], JIIA, 638, 6-15.

- Morgado, N. (2022). How can Geopolitical Agents restrain an Emerging Power’s Global and Regional Leadership? Evidence from Brazil. Geopoli-tics Quarterly 18(68), 268–298. https://dor.isc.ac/dor/20.1001.1.17354331.1401.18.68.12.4

- Morgado, N. (2023). Modelling Neoclassical Geopolitics: An Alternative Theoretical Tradition for Geopolitical Culture and Literacy. European Journal of Geography, 14(4), 13–21. https://doi.org/10.48088/ejg.n.mor.14.4.013.021.

- Morgado, N. & Hosoda, T. (2024). A Pact of Iron? China’s Deepening of the Sino-Russian Partnership. Frontiers in Political Science 6, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2024.1446054

- Morgado, N. & Druhalóczki, É. D. (2024). Traditional Worldviews, Strategic Culture, and Revolutionary Mentality: The Case of People’s Republic of China. China Report, 60(4), 361-377. https://doi.org/10.1177/00094455241288062

- Morgado, N. & Hosoda, T. (2025). Measuring Taiwan’s Power and Resilience: Capabilities, Strategic Culture, and Geopolitical Agents amid Cogni-tive Warfare. Asian International Studies Review 26(1), 85-108. https://doi.org/10.1163/2667078x-bja10043

- Murakami, T. (2009). Sengo nihon no heiwakyouiku no shakaigakuteki kenkyu [Sociological research on peace education in postwar Japan], Tokyo: Gakujutsu Shuppankai.

- National Institute for Materials Science. (2008). Wagakuni no toshikouzan ha sekaiyusu no shigenkokuni hitteki [Japan’s urban mines are compa-rable to those of the world's leading resource-rich countries], Press release on January 11, 2008. https://www.nims.go.jp/news/press/2008/01/200801110/p200801110.pdf

- Office of Fuel Distribution Policy. (2025). LP gas bichiku no joukyo [Current Status of LP Gas Stockpiling in March 2025]. https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/statistics/petroleum_and_lpgas/pl002/pdf/2025/250317lp.pdf

- Ogi, Y. (2024, April 24). Nihon-Bei-Go-Hi boei kyoryoku no shoten to naru nanboku shiren no chikeigaku [The geoeconomics of the North-South Sea Lane as a focal point of Japan-US-Australia-Philippines defence cooperation]. Institute of Geoeconomics. https://instituteofgeoeconomics.org/research/2024042557419/

- Okawa, Y. (2024). Kaiun to anzenhosho [Maritime transportation and national security]. Japan Maritime Self-Defence Force Staff College review,

- (2). https://doi.org/10.60415/mcscreview.13.2_18

- O’Shea, P. & Maslow, S. (2024). Rethinking change in Japan's security policy: punctuated equilibrium theory and Japan's response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Policy Studies, 45 (3-4), 653-676. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2024.2309218

- Fujiwara, O. (2015), Sengo heiwasyugi no igi to kadai [Unfulfilled Pacifism: Peace Movements in Postwar Japan], Peace Research, 45, 43-63. https://doi.org/10.50848/psaj.45004

- Palmer, J. (2010). Nihon no boueisangyo wa kongo ikani arubeki ka? [Which way now for the Japanese defense industry?], NIDS journal of de-fense and security, 12 (2&3), 115-145. https://www.nids.mod.go.jp/publication/kiyo/pdf/bulletin_j12-2-3_6.pdf

- Petroleum Refining and Stockpiling Division, Agency for Natural Resources and Energy. (2025). Sekiyu bichiku no genjo [Current Status of Petro-leum Stockpiling in March 2025]. https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/statistics/petroleum_and_lpgas/pl001/pdf/2025/250317oil.pdf

- Ruslin, R., Mashuri, S., Rasak, M. S. A., Alhabsyi, F., & Syam, H. (2022). Semi-structured interview: A methodological reflection on the develop-ment of a qualitative research instrument in educational studies. IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education (IOSR-JRME), 12(1), 22–29.

- Sakai, H. (2019). Return to geopolitics: The changes in Japanese strategic narratives, Asian Perspective, 43(2), 297–322. https://doi.org/10.1353/apr.2019.0012

- Sawa, J. (2023, May 16). Seifu bichikumai sakugen wo giron [Reduction of government stockpiled rice was discussed]. Nihon Keizai Shimbun. https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXZQOUB21CSV0R20C23A4000000/

- Study Group on Food Security in Emergency Situation. (2023). Fusokuji ni okeru Syokuryou Anzenhosyo ni Kansuru Kentokai Torimatome [Summary of Study Group on Food Security for unexpected situations]. https://www.maff.go.jp/j/zyukyu/anpo/attach/pdf/kentoukai-72.pdf

- Sugiyama, T. (2021, March 17.). Sekitan riyou no teishi ha kyukyoku no gusaku, Chugoku koso ga mondai no konnponn da [Stopping the use of coal is the ultimate folly. China is the root of the problem], Will. https://web-willmagazine.com/energy-environment/iWVwQ

- Sugiyama, T. (2023, March 14). Enerugi to shokuryo no ‘keisen nouryoku’ [Energy and food ‘capacity to continue the war’], Sankei Shimbun. https://www.sankei.com/article/20230314-TNJ3NQ5LJBNA5BRM3RMMXROIKQ/

- Szántó, Z. O., Aczél, P., Bóday, P., Csák, J., Ball, C., Farooqi, K., Hogan, D., & Pelsőci, B. L. (2024). The Future Potential Index for OECD Countries (2022). In: Morgado, N. & Kopanja, M. (Eds.), Geography, Identity, and Politics: Concepts, Theories, and Cases in Geopolitical Analysis. Belgrade University Press. https://doi.org/10.18485/ipsa_41_15.2024.7.ch2

- UNCTAD (2024). Review of Maritime Transport. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/rmt2024_en.pdf

- USINDOPACOM (2023). J06/SJA TACAID SERIES TOPIC: Naval Mine Warfare, 2. https://www.pacom.mil/Portals/55/Documents/Legal/J06%20TACAID%20-%20NAVAL%20MINE%20WARFARE%20-%20FINAL.pdf?ver=gLbgwiX0geT8vZdOEhZJLA%3D%3D

- Wirth, C. (2016). Securing the seas, securing the state: Hope, danger and the politics of order in the Asia-Pacific. Political Geography, 53, 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2016.02.002

- Wirth, C. (2017). Danger, development and legitimacy in East Asian maritime politics: Securing the seas, securing the state. Routledge.

- Yada, T. (1982). Nihon ni okeru sekitanshigen no hoki to saikaihatsu [Abandonment and Redevelopment of Coal Resources in Japan], Journal of Geography, 91(6), 77-83. https://doi.org/10.20592/jaeg.22.1_85

- Yamagoshi, N. (2023). Nihon shosentai no kakuho oyobi wagakuni no kokusaikaijoyuso ni okeru kadai [Securing the Japanese merchant fleet and issues in Japan's international maritime transportation]. Rippo to Chosa, 456, 35-47. https://www.sangiin.go.jp/japanese/annai/chousa/rippou_chousa/backnumber/2023pdf/20230428035.pdf